The Sampson and Delilah of American History

The brick building in this corner of what they called Pennsylvania scared him. The Lakota boy looked nervously up at it, his long fingernails habitually raking through his long hair. His scalp still smelled like the meadows and fires of home.

His mother had always been proud of his hair, his thick hair. It was like the grass of the prairies, long and strong, but dark as the night of the faceless moon.

When those men in dark blue had come to his village, when they had jumped off their tall horses and approached the nervous mothers, the boy’s fists had tightened. He had grabbed a log of firewood to mimic the war clubs of the warriors of his tribe. Warriors whose numbers had diminished in recent years.

But one man, this white man who approached, his fingers pink like a baby’s, his cheeks plump like melons, did not seem keen to practice that forceful white habit upon the Lakota women. He sought the chieftains, a council fire. His message was one of warning, that the white man was coming, either with guns loaded or eyes staring at the uncorrupted plains with hunger. With devilry or kindness, the white man was coming. The people, the great Lakota, had two options, to fight and die as they had done, or to learn from the white man.

This white man in blue had come to forewarn the chieftains, and as they sat in their teepee clouded in pipe smoke, he told them of a place in Pennsylvania. He wanted Lakota children to come to a school, to learn the ways of the white folk.

“Carlisle,” he called it. “Send the children to Carlisle, I will bring your children there, and they will come back knowing the ways of the white man. You will know how they think, how they plan to take your land. You can defend your people, the Lakota.”

On that long train ride from his home in Montana, the Lakota boy knew that again, his chiefs had fallen for the white lie. He had been sent, dressed in his buckskins, on the giant iron railroad beast. It rattled eastward towards his fate, one of death. The Lakota boy knew he would never return to Montana, to his mother, alive.

As the white soldiers issued the Lakota children off the train, the boy went up to one of them and spoke in his own tongue, “why do you take us here to kill us?”

The soldier looked down at the boy, his white face splattered with little red suns, universes of freckles. “Welcome home, little one,” the soldier said. That pale ghost of a man with the suns on his face showcased his toothless smile, a rancid breath that made the boy quiver in his buckskins.

“So it was true,” the Lakota boy thought, “this is where I go to die.”

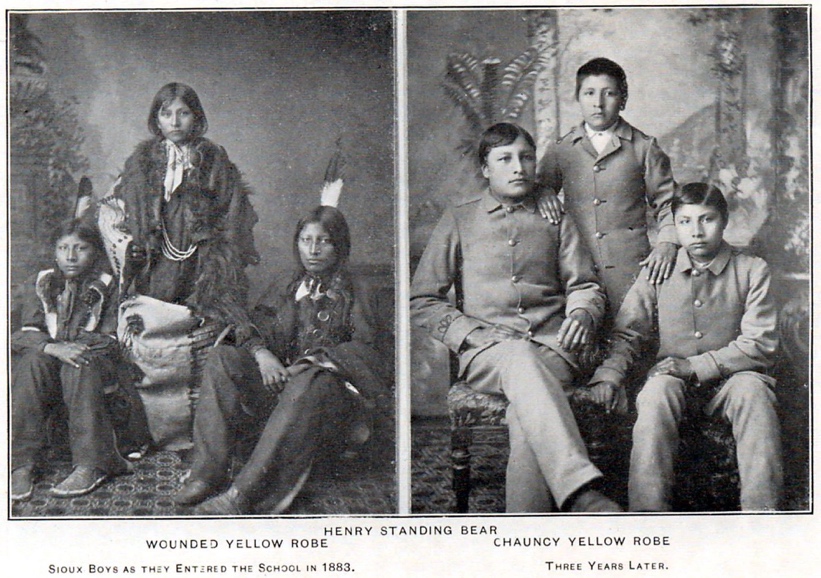

The soldiers ordered this group of native children into a long line. Ushered them into a stoic chess set formation, quietly vibrating with rattling fear. A man took a photograph, a loud flash and crack went off, and the immovable children fluttered in a flashing terror of death. The Lakota boy had a passing memory of when his uncle showed the size of the fish he had caught in the Mníšoše before gutting it.

“In here, in here,” said a woman in dark clothes, and she conducted her hands the way a shepherd shoos their flock. The young Lakota followed this herd of native children, which had grown with members of tribes from the Delaware, the Cherokee, the Crow, the Seneca, the Utes, and others that had been forced from their homes by the great, growing, hungry, cannibal monster that was the United States. She shooed them all towards a brick building.

The brick building in this corner of what they called Pennsylvania scared him. The Lakota boy looked nervously up at it, his long fingernails habitually raking through his long hair. His scalp still smelled like the meadows and fires of home. Huddled in the midst of the crowd of natives that were simultaneously strangers and kin in this frightful moment, the soldiers and other white people created a long line entering that evil, brooding brick house.

Inside was a white room. A black chair, a man with a white shirt and long, shining metal scissors.

“Here is where they kill me. Here is where I die for the Lakota, for the white man to possess me and my people. They won’t stop eating us all,” the boy thought to himself.

The man with the scissors beckoned to the crowd of children for a volunteer. Someone to sit in the black chair. None stepped forward.

There was a silence birthed from the collective gasp of breath from the children in their buckskins, moccasins, or cheap clothes. The man clicked his scissors together, and that snake tongue slither of metal on metal sunk into the bones of all who could hear it.

“I will go, for the Lakota,” the boy said in his own tongue. He whooped the air and banged his chest once. His chin high. He slowly stormed the black chair and sat, his neck raised, eyes closed, awaiting the cold death of the scissors.

He felt his hair being tugged, “a scalping then, like a true warrior, I will end,” he thought. But he never felt pain diving into his forehead. He felt only the light tugging of his hair, and the quick, yet delicate cutting of the scissor blades.

After a few minutes, the Lakota boy opened his eyes, terrified to see what was happening to him. In front of him, he saw himself, but not the self he recognized. He saw a native boy with a white devil’s hair. Not long and flowing or braided, but short and ordered and regimented in the way the whites did all things.

“Can nothing grow freely with you all?” The boy asked in his tongue. The barber only laughed at the words he could not comprehend and patted him on the shoulder. The haircut was over. But the Lakota boy could not move. He stared at his reflection, a reformed, re-forged version of himself.

“Will my mother love me without my hair? Am I still Lakota, or a bad copy of my killer?” he thought, staring at himself. “Will I still be one with the plains and the horses, with the sun and the moon, with the clouds and the sky? Will I still be one of my people now that these white people have taken me here and sheared me? Eaten my clothes, eaten my body, eaten my soul? Can I go back to the Lakota, can I go back a dead boy? Walking in new skin that isn’t mine, on old land I cannot claim. When the wind blows, does it say my name, my mother’s? Does it say America? Does it say Lakota? Or is it like I am now? Nameless?

The reflection of the Lakota boy disappeared and something new and nameless was refracted in the mirror. The weeping of the children began, the somber baying of humanity, stripped from itself into something it never could define in the first place. Nameless sorrow bleeding in Carlisle.